And still we rise. Foot after foot, metre after metre, round and around, like a bird of prey riding a thermal. Upward and onwards, higher and higher, every loop, every bend, every straight taking us into thinner and thinner air. Col, saddle, ridge, pass, we drive them all; and sometimes, you have to go down to go up. But the road keeps climbing. Endlessly.

Heaven and Hell

This is no ordinary driving environment. No way. Everything feels detached, otherworldly, dreamlike. Dazzling blue skies, craggy brown mountains and a narrow black ribbon of road. Nothing else. Everything you see is crisp, clean and vivid. Like it’s been colour-corrected for Instagram.

Out here in this rarefied spot, there are no ‘nannies’. No radar guns, no speed cameras, no speed limits. This is the sort of place where a supercar can run unmolested.

With no visual cues and no points of reference, it’s also easy to get up to silly speeds on the straight bits. The Beast of Bologna has 650hp, and on the freshly laid tarmac, I just want to place my foot on the floor every single chance I get. While doing 150-odd kph on some of the straighter bits is no sweat, I have to keep my wits about me around corners.

Speedo and tachometer apart, I also can’t keep my eyes away from the altimeter. The one we are using is our trusty old Garmin that right now is telling me we have crossed 19,000 feet. In a car. Which is nuts. I can’t get my head around the fact that we are around 5.8km above sea level. Imagine looking up and seeing an Urus instead of an Airbus. And a few kilometres above us is the stratosphere. This isn’t motoring, it’s aviation.

While we are some way from the ‘death zone’ that starts eight kilometres up, conditions here too are far from ideal. Oxygen levels are only 50 percent of that at sea level, which means you have to breathe twice as hard. Twice as hard when you are driving, twice as hard when you walk and, importantly, twice as hard when you exert yourself unnecessarily. Problem is, sometimes you can’t breathe twice as hard.

Also, once outside the car, it’s cold. Temperatures range between -5 and -10 degC when it’s warm, and after mid-morning, wind speeds pick up and can cross 60kph. What’s the temperature here towards the top in winter? It goes down to -45; and that’s without the wind chill. You can survive here, but not without consequences, and only for short intervals.

Welcome to Umling La, the highest motorable road in the world, and built by the Border Roads Organisation (BRO). To build a road at this altitude requires every bit of engineering ingenuity and tenacity. Temperatures here drop to -20 degC and, apart from sub-zero temperatures and biting winds, workers had to contend with the lack of oxygen. The construction machinery, too, worked at just 50-60 percent efficiency.

Beating the previous record of a road in Bolivia that spirals up the Uturuncu Volcano to 18,953 feet, Umling La at 19,300 feet above sea level can firmly lay claim to being the Mount Everest of roads. But where exactly is it?

Transport Stage

Our journey starts in Leh. The connecting flight from Chandigarh to Leh gives us a preview of the topography; tells us what to expect. First we wing over the Himalayan foothills. Green, hilly, verdant. Conifers, pines, deep ravines and pale blue streams. The transition is quick. The trees stop at around 4,000 metres. Soon after come the black and white peaks, snow and massive glacial flows. As we fly west, precipitation reduces, and less rain and less snow mean by the time the wheels touchdown in Leh, we are in a high-altitude desert.

Leh is also where we meet the Lamborghini Urus. I can all but imagine it opening its mouth and breathing fire... in true Ladakhi fashion. The first thing I check are the wheels. Thankfully, our Urus is running on 22-inch alloys and not 23 inchers with low-profile tyres. The tyres on the smaller 22-inch wheels come with taller sidewalls, a critically useful cushion against sharp edges, and that comes as a relief. What’s sure to help is the adjustable ride height and air suspension – a ground clearance of 248mm in ‘Terra’ mode is plenty. Pull back the Tamburo mode selector and the suspension moves up pretty smartly. Thank god, it isn’t some fiddly button on the touchscreen, because I can’t imagine what it’s like to operate the controls with gloves on. The next couple of days are spent relaxing in the hotel to help us acclimatise. Going from sea level to 3,500 metres in a matter of a few hours is quite a hop, and our heads are spinning.

Day one of our journey involves something of a transport stage. We leave early for Hanle (4,300m), but stop at the BRO’s (Border Roads Organisation) regional headquarters right outside the city to pay homage at a memorial, built to all the workers who’ve lost their lives making these roads. The sombre plaque is a chilling reminder of what the BRO is up against. These are conditions not to be scoffed at. The altitude, freezing temperature, the lack of oxygen: any of these can kill you. And when you are out, exposed for hours, you have to deal with all of these hostile elements at the same time.

Next stop is Thiksey Monastery which we stop at for a great photo op. The bright yellow Urus contrasts sharply against the dazzling white gompas and brilliant blue skies for the perfect Instagram post.

Up ahead, the road to Hanle follows the river Indus for a magical 200-odd kilometres – every twist, every turn, every long straight right alongside the river. This, incredibly, is also where the landmass of India is pushed up against the landmass of Asia, creating the Himalayas 50 million years ago. Along the river, you’ll find all manner of flora and fauna – the Wild Ass or Kiang, Blue Sheep or Bharal, Ladakh Urial, Bearded Vultures and the Tibetan gazelle, among others.

The Climb begins

Hanle feels like a small town on the fringes of the galaxy, one straight out of Star Wars, where if you walk into a bar, you are sure to meet all manner of intelligent life forms. A centre for astronomy in India, with some of the highest telescopes and gamma ray observatories situated here, it is a place where electricity is switched off at 11pm to help reduce light pollution.

With winds picking up at mid-morning on the Umling La pass, we decide to leave early. Our early start means we also get front row seats to the great gig in the sky – we get to see our galaxy, the Milky Way! A dull white band of stars stretching all the way from one horizon to the other, this sight fills me with wonder.

What we are looking at is probably one of the arms of our spiral galaxy and some part of the disc. Just incredible.

The first part of our trip today is a shallow climb across a long valley. With no fixed track and several dirt roads leading up, we are free to take whichever route we choose. We stick to the well-beaten path and stay on the tracks made by trucks, Gypsys, Safaris and Boleros of the Indian Army and the BRO. Imagine getting lost here. No telephones, no dhabas, no people, nothing. All we have for company are the howling winds. We cross only a Tata pick-up during the day. One. The desolation is other worldly.

In places, the valley floor is littered with sharp rocks, and here we have to be careful because of the tyres. But the topography changes every few kilometres and as soon as we hit a smoother section all I want to do is flatten my foot on the floor. And that’s exactly what I do. What a competitive or special stage this would make. Sand, gravel, grit, stones and, at times, over the flatter section of the dry lakes, the ability to do some insane triple-digit speeds.

Wonder why you wouldn’t want to get the fastest, most extreme car possible here. To celebrate the road, enjoy it, revel in its uniqueness. Thank god, we got the Urus. Coming here in something ordinary would have been such a waste. So pointless, so humdrum.

Push to the summit

After around 30km, we finally come upon freshly laid tarmac; we take a 90-degree left and that’s where the real climb begins. The gradient isn’t very steep. This ribbon of tarmac has been built for heavy equipment. Very heavy equipment. So the shallower the angle, the easier it is for these ‘essential services’ to power up and over the pass. But remember, with oxygen levels only at 50 percent, you can only make 50 percent power. Unless you have a turbo, that is.

The Urus has two. And both use twin scrolls, which sort of helps. I switch the Tamburo back to Strada or street as soon as we get on to the tarmac, and before long can’t resist switching to Sport for brief stretches. All worries on how the highly strung and marginal V8 will perform at this altitude go out of the window. The engine is as responsive as it is at sea level and pulls clean and hard, punching like a sledgehammer when you keep your foot down. And there’s no hesitation, whatsoever; not something we expected, especially after our experience with a pair of luxury diesel SUVs, a few years ago.

I have to admit, I do get carried away. More than a bit. Don’t know if it’s the lack of oxygen, the headache or the slight disorientation, but I start imagining I’m at Pikes Peak, chasing time. There’s no margin for error here, however. The road is narrow, the straights are long, and since corners sometimes arrive quickly you have to be both quick on the brakes and the steering. And then, letting the horses out of the door, all 650 of them at the same time, isn’t a good idea either. You have to feed in the power carefully on the way out.

Despite having to take it a notch down, this still is incredibly thrilling, flying up the pass. I regularly use all the revs in the first few gears. I use the paddles to thump-shift to the next gear in Corsa – because it feels great, and then every time I go down the ‘box, the quad exhausts pop and bang on overrun, ricocheting off the craggy mountains. Lamborghini and drama, they go hand in hand, yes, but this is high drama, drama on a grand scale. And the canvas is so vast, you just feel like a spec here; on the roof of the world, all alone in the wide blue yonder.

On the roof

Then we pass a board that says: “You are now higher than Everest Base Camp.” That sounds crazy! And, of course, we stop and take some pictures. We are soon, however, on our way again. We have a date at the top of the pass with the BRO. They’ve organised tea. At 19,300 feet!

Once we get there, it’s much more than tea. We are honoured with a flag hoisting ceremony, which is very emotional. Although we should spend only a few minutes at the top, we’re there for much longer. Soon, we all develop dull headaches due to the altitude. That the BRO could build such a smooth road in sub-zero, oxygen-starved altitudes, where just walking is an exhausting task, one can only imagine what it’s like to break rocks and pave tarmac in these extreme conditions. Umling La is a true tribute to human endurance. The BRO must be saluted for this monumental achievement.

Border Roads Organisation (BRO): strategic road builders to the nation

Tasked with building roads in difficult conditions in and around our borders, the BRO is a road construction executive force that is an integral part of the Indian Defence forces. Created to construct and maintain roads classified as General Staff (GS) roads and fulfil the strategic needs of the armed forces, the BRO’s role today is expanding to include all manner of strategic infrastructure projects. The BRO also builds bridges, overpasses, tunnels, airfields and advanced landing grounds. When the weather turns bad the BRO are even responsible for clearing the snow and opening the road again. As you can imagine, both civil engineers and mechanical engineers are recruited into the BRO. The BRO also has a sharp focus on safety. Many of its safety messages, signposted in bold letters along the road, are witty and get you to laugh, but also drive home the message effectively

In conversation with Hemant Singh, Commander, Border Roads Task Force

The Commander of the Border Roads Task Force tells us, on top of the Umling La pass, how this road was made.

Firstly, what was the objective behind building something like this, the highest motorable road in the world?

The Border Roads Organisation has been tasked with bringing connectivity to every remote corner of India. Places like Chisumle and Demchok in Ladakh lie at the fringes, and earlier, it took two to three days to reach by mule track. They can now be reached in two or three hours. This road also helps with the quick induction of armed forces and is important in building the economy of the place.

Were any special materials and tech used to build this road, especially to prevent it from breaking up in winter?

Yes. While on other roads, a Granular Sub-Base (GSB) of sand, gravel and crushed stone is used below the road, here we have used a non-frost-susceptible sub-base. So now, even though we get eight to ten feet of snow in winter, the road doesn’t break up. And this is because water is not allowed to rise up through the road, due to capillary action, and damage it.

What were the physical challenges? Because this seems to be a road where human endurance has really been tested.

As you can see yourself, even though we are standing in bright sunshine, the temperature currently is -4 to -5 degC, and the wind is so high, we are unable to speak freely. So it is actually a test of human endurance, manpower and willpower here.

The biggest problem is that in winter, temperatures go down to -35 or -40 degC, and then, because of the high altitude and low oxygen, we have to rotate both people and machines, and only use them on alternate days.

And what would be the most challenging part of this road?

The most challenging part is the last 20-30 percent, which is on top of the world. That is where the wind and chill factor is very, very high.

Hormazd Sorabjee

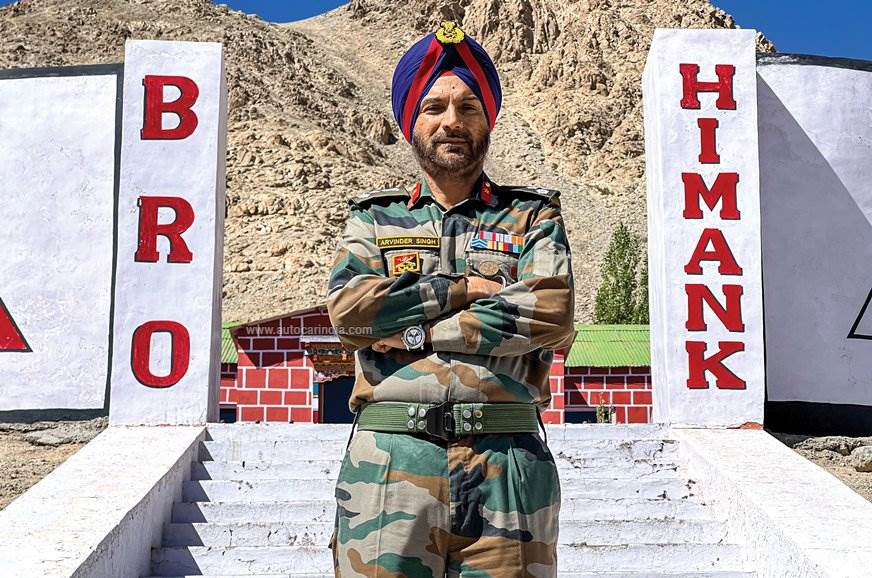

In conversation with Brigadier Arvinder Singh, Chief Engineer, Border Roads Organisation, Project Himank.

The world’s highest motorable pass, the Mount Everest of passes, Umling La at 19,300 feet has been built under impossible and challenging conditions. Tell us about the challenges.

At 19,300 feet, the biggest challenge is that you get only a short span of time to finish the bulk of your work. In summer, you can work for only five months. During this period, we have to do the blacktop work and the cement work. But to build the road, we also have to work in winters when the temperatures go down to -45 degC. During winter time, we do all of our formation work, levelling of the road and laying of the sub-base.

Another big challenge is that there is very little oxygen here; 50 percent less than what it is normally at sea level! As a result, the efficiency of both man and machine is reduced by half.

The third major challenge is that, due to the low oxygen levels, we have a lot of medical issues with the people who are working on the road. These high-altitude related diseases and problems are so bad, we have to continuously rotate our manpower. So the construction of this road shows the endurance of human spirit, the never-say-die attitude of the BRO, who made a landmark on the world stage by constructing 52km of blacktop all the way up to 19,300 feet.

Hormazd Sorabjee

https://ift.tt/3cH7lAb